streda 13. augusta 2008

Efortless English Club

What is the most important English skill? What skill must you have to communicate well?

Obviously, number 1 is Fluency. What is fluency? Fluency is the ability to speak (and understand)

English quickly and easily... WITHOUT translation. Fluency means you can talk easily with native

speakers-- they easily understand you, and you easily understand them. In fact, you speak and

understand instantly.

Fluency is your most important English goal.

The research is clear-- there is only ONE way to get fluency. You do not get fluency by reading textbooks.

You do not get fluency by going to English schools. You do not get fluency by studying

grammar rules.

Listening Is The Key

To get English fluency, you must have a lot of understandable repetitive listening. That is the

ONLY way. To be a FANTASTIC English speaker, you must learn English with your ears, not with

your eyes. In other words, you must listen. Your ears are the key to excellent speaking.

What kind of listening is best? Well, it must be understandable and must be repetitive. Both of

those words are important-- Understandable and Repetitive.

If you don't understand, you learn nothing. You will not improve. That's why listening to English TV

does not help you. You don't understand most of it. It is too difficult. It is too fast.

Its obvious right? If you do not understand, you will not improve. So, the best listening material is

EASY. That’s right, you should listen mostly to easy English. Most students listen to English that is

much too difficult. They don’t understand enough, and so they learn slowly. Listen to easier English,

and your speaking will improve faster!

Understanding is Only Half The Formula.

Understanding is not enough. You must also have a lot of repetition. If you hear a new word only

once, you will soon forget it. If you hear it 5 times, you will still probably forget it!

You must hear new words and new grammar many times before you will understand them

instantly.

How many times is necessary? Most people must hear a new word 30 times to remember it forever.

To know a word and instantly understand it, you probably need to hear it 50-100 times!

The Key To Excellent Speaking

www.EffortlessEnglishClub.com

That's why I tell my students to listen to all of my lessons many times. I tell them to listen to the

Mini-Stories, the Vocab Lessons, The Point-of-View Stories, and the Audio articles everyday. I recommend

that they listen to each lesson a total of 30 times (for example, 2 times a day for two

weeks).

So, the two most important points are: listen to easier English and listen to each thing many

times.

Suggestions For Powerful Listening and Excellent Speaking

1. Practice “Narrow Listening”

“Narrow listening” means listening to many things about the same topic. This method is more powerful

than trying to listen to many different kinds of things. Students who listen to similar things learn

faster and speak better than students who listen to different kinds of things.

For example, you can choose one speaker and find many things by him. Listen to all of his podcasts,

audio books, and speeches. This is powerful because all speakers have favorite vocabulary

and grammar. They naturally repeat these many times. By listening to many things by the same

person, you automatically get a lot of vocabulary repetition. You learn faster and deeper!

Another example is to choose one topic to focus on. For example, you could read an easy book, listen

to the same audio book, listen to a podcast about the book, and watch the movie.

I did this with my class in San Francisco. We read “Charlie and the Chocolate Factory”. Then we

listened to the audio book. Then we watched (and listened to) the movie. Then we listened to interviews

with actors in the movie. My students learned a lot of vocabulary in a short time, and their

speaking improved very quickly.

2. Divide Your Listening Time

Which is better: to listen for two hours without a break, or to divide that time during the day? Well,

dividing your listening time is best.

By dividing your time throughout the day, you remember more and learn faster. So its much better

to listen 30 minutes in the morning, then 30 minutes in the car or train, then 30 minutes coming

home from work, then 30 minutes before sleep. In fact, this is the exact schedule I recommend to

my students!

3. Use an iPod or MP3 Player

iPods are fantastic. You can put a big listening library on one. Then you can carry your English lessons

everywhere. You can learn English while walking, while shopping, in the car, in a train, while

cooking,.......

With an iPod or MP3 player, you don’t have to worry about CDs. Also, you can find a lot of English

www.EffortlessEnglishClub.com

listening on the internet. You can find lessons, stories, podcasts, TV shows, interviews, and audio

books. Simply download the audio, put it on your iPod.. and learn English anywhere!

4. Listen To Movies

Movies are great for learning English BUT you must use them correctly. Don’t watch all of an

English movie. You will not understand it, and therefore you will not learn anything.

Only watch one scene or segment per week (maybe 2-3 minutes). Follow this method:

a) First, watch the scene with subtitles in your language. This will help you understand the general

meaning.

b) Second, watch the scene with English subtitles. Pause. Use a dictionary to find new words you

don’t understand. Write the new sentences in a notebook.

c) Listen to the scene a few times, with English subtitles. Do not pause.

d) Listen to the scene a few times, without subtitles.

e) Repeat a) - d) everyday for one week.

On the second week, go to the next scene/segment and repeat again. It will take you a long time to

finish a movie. That’s OK, because you will improve your listening and speaking VERY FAST. This

method is powerful-- use it!

5. Read and Listen at the Same Time

Listening and Reading together are very powerful. While you listen to something, also read it. This

will improve your pronunciation.

Reading while listening also helps you understand more difficult material. Read and listen to learn

faster. After you do this a few times, put away the text and just listen. You will understand a lot

more and you will improve faster. Always try to find both audio and text materials.

To start, you can read my blog and listen to my podcast at:

Text

http://www.EffortlessEnglishClub.blogspot.com

Audio

http://www.EffortlessEnglish.libsyn.com

Another great idea is to get both a book and its audio book (ie. the above example of “Charlie and

the Chocolate Factory”).

6 Months To Excellent English Speaking

Follow the above suggestions (and the 7 Rules in my email course) and you will speak excellent

English.

I have been teaching over 10 years. Every student who follows these methods succeeds. Always!

The Effortless English method is the key to speaking excellent English. It is the key to fluency.

www.EffortlessEnglishClub.com

You only need 6 months-- 6 months and you will speak easily to native speakers. 6 months and

you will speak quickly and naturally. 6 months and you feel relaxed when you speak English.

You have tried the old ways. You tried textbooks. You tried schools. You tried grammar study.

It is time to try something new!

Good luck. I wish you success with your English learning!

A.J. Hoge

Director

Effortless English

www.EffortlessEnglishClub.com

Listening & Learning Resources On The Internet

7 Rules of Effortless English (Free Email Course)

http://www.EffortlessEnglishClub.com/free.html

The Effortless English Podcast (Listening)

http://www.EffortlessEnglish.libsyn.com

The Effortless English Blog (Text for Audio)

http://www.EffortlessEnglishClub.blogspot.com

Effortless English Lessons (Listening and Text)

http://www.EffortlessEnglishClub.com

Flow English Lessons (Listening and Text)

http://www.EffortlessEnglishClub.com/flowenglish.html

LingQ (Listening and Tutors)

http://www.lingq.com

ELLLO (Listening)

http://www.elllo.org

KanTalk (Internet Chats and Conversation)

http://www.kantalk.com

VOA News (Listening)

http://www.voanews.com/english/podcasts.cfm

Business English Pod (Listening)

http://www.voanews.com/english/podcasts.cfm

ESL Pod (Listening)

http://www.eslpod.com

Just Vocabulary (Listening)

http://justvocabulary.libsyn.com/

www.EffortlessEnglishClub.com

pondelok 11. augusta 2008

Through the looking glass - Chapter 1

Looking-Glass House. Alice’s out of the way adventures start again in the second Alice book by Lewis Carroll, published in 1871.

Looking-Glass House. Alice’s out of the way adventures start again in the second Alice book by Lewis Carroll, published in 1871.

This time she meets characters from a game of chess - as opposed to the pack of cards in the first book. There are more jokes based on bending logic, and we can look forward to plenty of conundrums.

In the opening scene, Alice is playing with her cats and a ball of wool (worsted). This might well have been written from observation. Lewis Carroll’s real name was Charles Dodgson, and he was tutor at Christchurch College, Oxford. He befriended Alice Liddell, the pretty and clever daughter of the College’s Dean. And Alice really did have a cat called Dinah.

But the highlight of the chapter is surely one of the most brilliant pieces of nonsense ever written. The poem called

“JABBERWOCKY” which begins ‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves..”

Read, of course, by Natasha. Duration 23.10.

CHAPTER 1

Looking-Glass House

One thing was certain, that the WHITE kitten had had nothing to

do with it:–it was the black kitten’s fault entirely. For the

white kitten had been having its face washed by the old cat for

the last quarter of an hour (and bearing it pretty well,

considering); so you see that it COULDN’T have had any hand in

the mischief.

The way Dinah washed her children’s faces was this: first she

held the poor thing down by its ear with one paw, and then with

the other paw she rubbed its face all over, the wrong way,

beginning at the nose: and just now, as I said, she was hard at

work on the white kitten, which was lying quite still and trying

to purr–no doubt feeling that it was all meant for its good.

But the black kitten had been finished with earlier in the

afternoon, and so, while Alice was sitting curled up in a corner

of the great arm-chair, half talking to herself and half asleep,

the kitten had been having a grand game of romps with the ball of

worsted Alice had been trying to wind up, and had been rolling it

up and down till it had all come undone again; and there it was,

spread over the hearth-rug, all knots and tangles, with the

kitten running after its own tail in the middle.

‘Oh, you wicked little thing!’ cried Alice, catching up the

kitten, and giving it a little kiss to make it understand that it

was in disgrace. ‘Really, Dinah ought to have taught you better

manners! You OUGHT, Dinah, you know you ought!’ she added,

looking reproachfully at the old cat, and speaking in as cross a

voice as she could manage–and then she scrambled back into the

arm-chair, taking the kitten and the worsted with her, and began

winding up the ball again. But she didn’t get on very fast, as

she was talking all the time, sometimes to the kitten, and

sometimes to herself. Kitty sat very demurely on her knee,

pretending to watch the progress of the winding, and now and then

putting out one paw and gently touching the ball, as if it would

be glad to help, if it might.

‘Do you know what to-morrow is, Kitty?’ Alice began. ‘You’d

have guessed if you’d been up in the window with me–only Dinah

was making you tidy, so you couldn’t. I was watching the boys

getting in sticks for the bonfire–and it wants plenty of

sticks, Kitty! Only it got so cold, and it snowed so, they had

to leave off. Never mind, Kitty, we’ll go and see the bonfire

to-morrow.’ Here Alice wound two or three turns of the worsted

round the kitten’s neck, just to see how it would look: this led

to a scramble, in which the ball rolled down upon the floor, and

yards and yards of it got unwound again.

‘Do you know, I was so angry, Kitty,’ Alice went on as soon as

they were comfortably settled again, ‘when I saw all the mischief

you had been doing, I was very nearly opening the window, and

putting you out into the snow! And you’d have deserved it, you

little mischievous darling! What have you got to say for

yourself? Now don’t interrupt me!’ she went on, holding up one

finger. ‘I’m going to tell you all your faults. Number one:

you squeaked twice while Dinah was washing your face this

morning. Now you can’t deny it, Kitty: I heard you! What’s that

you say?’ (pretending that the kitten was speaking.) ‘Her paw

went into your eye? Well, that’s YOUR fault, for keeping your

eyes open–if you’d shut them tight up, it wouldn’t have

happened. Now don’t make any more excuses, but listen! Number

two: you pulled Snowdrop away by the tail just as I had put down

the saucer of milk before her! What, you were thirsty, were you?

How do you know she wasn’t thirsty too? Now for number three:

you unwound every bit of the worsted while I wasn’t looking!

‘That’s three faults, Kitty, and you’ve not been punished for

any of them yet. You know I’m saving up all your punishments for

Wednesday week–Suppose they had saved up all MY punishments!’

she went on, talking more to herself than the kitten. ‘What

WOULD they do at the end of a year? I should be sent to prison,

I suppose, when the day came. Or–let me see–suppose each

punishment was to be going without a dinner: then, when the

miserable day came, I should have to go without fifty dinners at

once! Well, I shouldn’t mind THAT much! I’d far rather go

without them than eat them!

‘Do you hear the snow against the window-panes, Kitty? How

nice and soft it sounds! Just as if some one was kissing the

window all over outside. I wonder if the snow LOVES the trees

and fields, that it kisses them so gently? And then it covers

them up snug, you know, with a white quilt; and perhaps it says,

“Go to sleep, darlings, till the summer comes again.” And when

they wake up in the summer, Kitty, they dress themselves all in

green, and dance about–whenever the wind blows–oh, that’s

very pretty!’ cried Alice, dropping the ball of worsted to clap

her hands. ‘And I do so WISH it was true! I’m sure the woods

look sleepy in the autumn, when the leaves are getting brown.

‘Kitty, can you play chess? Now, don’t smile, my dear, I’m

asking it seriously. Because, when we were playing just now, you

watched just as if you understood it: and when I said “Check!”

you purred! Well, it WAS a nice check, Kitty, and really I might

have won, if it hadn’t been for that nasty Knight, that came

wiggling down among my pieces. Kitty, dear, let’s pretend–’

And here I wish I could tell you half the things Alice used to

say, beginning with her favourite phrase ‘Let’s pretend.’ She

had had quite a long argument with her sister only the day before

–all because Alice had begun with ‘Let’s pretend we’re kings

and queens;’ and her sister, who liked being very exact, had

argued that they couldn’t, because there were only two of them,

and Alice had been reduced at last to say, ‘Well, YOU can be one

of them then, and I’LL be all the rest.’ And once she had really

frightened her old nurse by shouting suddenly in her ear, ‘Nurse!

Do let’s pretend that I’m a hungry hyaena, and you’re a bone.’

But this is taking us away from Alice’s speech to the kitten.

‘Let’s pretend that you’re the Red Queen, Kitty! Do you know, I

think if you sat up and folded your arms, you’d look exactly like

her. Now do try, there’s a dear!’ And Alice got the Red Queen

off the table, and set it up before the kitten as a model for it

to imitate: however, the thing didn’t succeed, principally,

Alice said, because the kitten wouldn’t fold its arms properly.

So, to punish it, she held it up to the Looking-glass, that it

might see how sulky it was–’and if you’re not good directly,’

she added, ‘I’ll put you through into Looking-glass House. How

would you like THAT?’

‘Now, if you’ll only attend, Kitty, and not talk so much, I’ll

tell you all my ideas about Looking-glass House. First, there’s

the room you can see through the glass–that’s just the same as

our drawing room, only the things go the other way. I can see

all of it when I get upon a chair–all but the bit behind the

fireplace. Oh! I do so wish I could see THAT bit! I want so

much to know whether they’ve a fire in the winter: you never CAN

tell, you know, unless our fire smokes, and then smoke comes up

in that room too–but that may be only pretense, just to make

it look as if they had a fire. Well then, the books are

something like our books, only the words go the wrong way; I know

that, because I’ve held up one of our books to the glass, and

then they hold up one in the other room.

‘How would you like to live in Looking-glass House, Kitty? I

wonder if they’d give you milk in there? Perhaps Looking-glass

milk isn’t good to drink–But oh, Kitty! now we come to the

passage. You can just see a little PEEP of the passage in

Looking-glass House, if you leave the door of our drawing-room

wide open: and it’s very like our passage as far as you can see,

only you know it may be quite different on beyond. Oh, Kitty!

how nice it would be if we could only get through into Looking-

glass House! I’m sure it’s got, oh! such beautiful things in it!

Let’s pretend there’s a way of getting through into it, somehow,

Kitty. Let’s pretend the glass has got all soft like gauze, so

that we can get through. Why, it’s turning into a sort of mist

now, I declare! It’ll be easy enough to get through–’ She

was up on the chimney-piece while she said this, though she

hardly knew how she had got there. And certainly the glass WAS

beginning to melt away, just like a bright silvery mist.

In another moment Alice was through the glass, and had jumped

lightly down into the Looking-glass room. The very first thing

she did was to look whether there was a fire in the fireplace,

and she was quite pleased to find that there was a real one,

blazing away as brightly as the one she had left behind. ‘So I

shall be as warm here as I was in the old room,’ thought Alice:

‘warmer, in fact, because there’ll be no one here to scold me

away from the fire. Oh, what fun it’ll be, when they see me

through the glass in here, and can’t get at me!’

Then she began looking about, and noticed that what could be

seen from the old room was quite common and uninteresting, but

that all the rest was as different as possible. For instance, the

pictures on the wall next the fire seemed to be all alive, and

the very clock on the chimney-piece (you know you can only see

the back of it in the Looking-glass) had got the face of a little

old man, and grinned at her.

‘They don’t keep this room so tidy as the other,’ Alice thought

to herself, as she noticed several of the chessmen down in the

hearth among the cinders: but in another moment, with a little

‘Oh!’ of surprise, she was down on her hands and knees watching

them. The chessmen were walking about, two and two!

‘Here are the Red King and the Red Queen,’ Alice said (in a

whisper, for fear of frightening them), ‘and there are the White

King and the White Queen sitting on the edge of the shovel–and

here are two castles walking arm in arm–I don’t think they can

hear me,’ she went on, as she put her head closer down, ‘and I’m

nearly sure they can’t see me. I feel somehow as if I were

invisible–’

Here something began squeaking on the table behind Alice, and

made her turn her head just in time to see one of the White Pawns

roll over and begin kicking: she watched it with great

curiosity to see what would happen next.

‘It is the voice of my child!’ the White Queen cried out as she

rushed past the King, so violently that she knocked him over

among the cinders. ‘My precious Lily! My imperial kitten!’ and

she began scrambling wildly up the side of the fender.

‘Imperial fiddlestick!’ said the King, rubbing his nose, which

had been hurt by the fall. He had a right to be a LITTLE annoyed

with the Queen, for he was covered with ashes from head to foot.

Alice was very anxious to be of use, and, as the poor little

Lily was nearly screaming herself into a fit, she hastily picked

up the Queen and set her on the table by the side of her noisy

little daughter.

The Queen gasped, and sat down: the rapid journey through the

air had quite taken away her breath and for a minute or two she

could do nothing but hug the little Lily in silence. As soon as

she had recovered her breath a little, she called out to the

White King, who was sitting sulkily among the ashes, ‘Mind the

volcano!’

‘What volcano?’ said the King, looking up anxiously into the

fire, as if he thought that was the most likely place to find

one.

‘Blew–me–up,’ panted the Queen, who was still a little

out of breath. ‘Mind you come up–the regular way–don’t get

blown up!’

Alice watched the White King as he slowly struggled up from bar

to bar, till at last she said, ‘Why, you’ll be hours and hours

getting to the table, at that rate. I’d far better help you,

hadn’t I?’ But the King took no notice of the question: it was

quite clear that he could neither hear her nor see her.

So Alice picked him up very gently, and lifted him across more

slowly than she had lifted the Queen, that she mightn’t take his

breath away: but, before she put him on the table, she thought

she might as well dust him a little, he was so covered with

ashes.

She said afterwards that she had never seen in all her life

such a face as the King made, when he found himself held in the

air by an invisible hand, and being dusted: he was far too much

astonished to cry out, but his eyes and his mouth went on getting

larger and larger, and rounder and rounder, till her hand shook

so with laughing that she nearly let him drop upon the floor.

‘Oh! PLEASE don’t make such faces, my dear!’ she cried out,

quite forgetting that the King couldn’t hear her. ‘You make me

laugh so that I can hardly hold you! And don’t keep your mouth

so wide open! All the ashes will get into it–there, now I

think you’re tidy enough!’ she added, as she smoothed his hair,

and set him upon the table near the Queen.

The King immediately fell flat on his back, and lay perfectly

still: and Alice was a little alarmed at what she had done, and

went round the room to see if she could find any water to throw

over him. However, she could find nothing but a bottle of ink,

and when she got back with it she found he had recovered, and he

and the Queen were talking together in a frightened whisper–so

low, that Alice could hardly hear what they said.

The King was saying, ‘I assure, you my dear, I turned cold to

the very ends of my whiskers!’

To which the Queen replied, ‘You haven’t got any whiskers.’

‘The horror of that moment,’ the King went on, ‘I shall never,

NEVER forget!’

‘You will, though,’ the Queen said, ‘if you don’t make a

memorandum of it.’

Alice looked on with great interest as the King took an

enormous memorandum-book out of his pocket, and began writing. A

sudden thought struck her, and she took hold of the end of the

pencil, which came some way over his shoulder, and began writing

for him.

The poor King looked puzzled and unhappy, and struggled with the

pencil for some time without saying anything; but Alice was too

strong for him, and at last he panted out, ‘My dear! I really

MUST get a thinner pencil. I can’t manage this one a bit; it

writes all manner of things that I don’t intend–’

‘What manner of things?’ said the Queen, looking over the book

(in which Alice had put ‘THE WHITE KNIGHT IS SLIDING DOWN THE

POKER. HE BALANCES VERY BADLY’) ‘That’s not a memorandum of

YOUR feelings!’

There was a book lying near Alice on the table, and while she

sat watching the White King (for she was still a little anxious

about him, and had the ink all ready to throw over him, in case

he fainted again), she turned over the leaves, to find some part

that she could read, ‘–for it’s all in some language I don’t

know,’ she said to herself.

It was like this.

YKCOWREBBAJ

sevot yhtils eht dna ,gillirb sawT’

ebaw eht ni elbmig dna eryg diD

,sevogorob eht erew ysmim llA

.ebargtuo shtar emom eht dnA

She puzzled over this for some time, but at last a bright

thought struck her. ‘Why, it’s a Looking-glass book, of course!

And if I hold it up to a glass, the words will all go the right

way again.’

This was the poem that Alice read.

JABBERWOCKY

‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

‘Beware the Jabberwock, my son!

The jaws that bite, the claws that catch!

Beware the Jubjub bird, and shun

The frumious Bandersnatch!’

He took his vorpal sword in hand:

Long time the manxome foe he sought–

So rested he by the Tumtum tree,

And stood awhile in thought.

And as in uffish thought he stood,

The Jabberwock, with eyes of flame,

Came whiffling through the tulgey wood,

And burbled as it came!

One, two! One, two! And through and through

The vorpal blade went snicker-snack!

He left it dead, and with its head

He went galumphing back.

‘And hast thou slain the Jabberwock?

Come to my arms, my beamish boy!

O frabjous day! Callooh! Callay!’

He chortled in his joy.

‘Twas brillig, and the slithy toves

Did gyre and gimble in the wabe;

All mimsy were the borogoves,

And the mome raths outgrabe.

‘It seems very pretty,’ she said when she had finished it, ‘but

it’s RATHER hard to understand!’ (You see she didn’t like to

confess, ever to herself, that she couldn’t make it out at all.)

‘Somehow it seems to fill my head with ideas–only I don’t

exactly know what they are! However, SOMEBODY killed SOMETHING:

that’s clear, at any rate–’

‘But oh!’ thought Alice, suddenly jumping up, ‘if I don’t make

haste I shall have to go back through the Looking-glass, before

I’ve seen what the rest of the house is like! Let’s have a look

at the garden first!’ She was out of the room in a moment, and

ran down stairs–or, at least, it wasn’t exactly running, but a

new invention of hers for getting down stairs quickly and easily,

as Alice said to herself. She just kept the tips of her fingers

on the hand-rail, and floated gently down without even touching

the stairs with her feet; then she floated on through the hall,

and would have gone straight out at the door in the same way, if

she hadn’t caught hold of the door-post. She was getting a

little giddy with so much floating in the air, and was rather

glad to find herself walking again in the natural way.

Alice in wonderland - Chapter 12

Download the MP3 Audio (right click, save as)

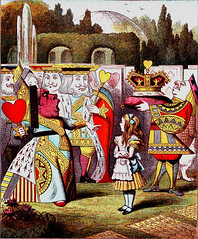

Alice’s Evidence We reach the final Chapter of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland - but don’t worry - there are more adventures to come “Through The Looking Glass”.Justice is not exactly done in this Wonderland trial - in fact Alice is infuriated by the lack of it. She is growing again in stature and in confidence, and is provoked to shout her famous line: “You’re nothing but a pack of cards!”The lyrical epilogue is in a different vein to the rest of Alice -perhaps a touch of Victoriana - but it brings the book to a suitably reamy conclusion.Read by Natasha. Duration 17.23 `Here!’ cried Alice, quite forgetting in the flurry of themoment how large she had grown in the last few minutes, and shejumped up in such a hurry that she tipped over the jury-box withthe edge of her skirt, upsetting all the jurymen on to the headsof the crowd below, and there they lay sprawling about, remindingher very much of a globe of goldfish she had accidentally upset the week before.

Alice’s Evidence We reach the final Chapter of Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland - but don’t worry - there are more adventures to come “Through The Looking Glass”.Justice is not exactly done in this Wonderland trial - in fact Alice is infuriated by the lack of it. She is growing again in stature and in confidence, and is provoked to shout her famous line: “You’re nothing but a pack of cards!”The lyrical epilogue is in a different vein to the rest of Alice -perhaps a touch of Victoriana - but it brings the book to a suitably reamy conclusion.Read by Natasha. Duration 17.23 `Here!’ cried Alice, quite forgetting in the flurry of themoment how large she had grown in the last few minutes, and shejumped up in such a hurry that she tipped over the jury-box withthe edge of her skirt, upsetting all the jurymen on to the headsof the crowd below, and there they lay sprawling about, remindingher very much of a globe of goldfish she had accidentally upset the week before.

`Oh, I BEG your pardon!’ she exclaimed in a tone of greatdismay, and began picking them up again as quickly as she could,for the accident of the goldfish kept running in her head, andshe had a vague sort of idea that they must be collected at onceand put back into the jury-box, or they would die.

`The trial cannot proceed,’ said the King in a very gravevoice, `until all the jurymen are back in their proper places–ALL,’ he repeated with great emphasis, looking hard at Alice ashe said do.

Alice looked at the jury-box, and saw that, in her haste, shehad put the Lizard in head downwards, and the poor little thingwas waving its tail about in a melancholy way, being quite unableto move. She soon got it out again, and put it right; `not thatit signifies much,’ she said to herself; `I should think itwould be QUITE as much use in the trial one way up as the other.’

As soon as the jury had a little recovered from the shock ofbeing upset, and their slates and pencils had been found andhanded back to them, they set to work very diligently to writeout a history of the accident, all except the Lizard, who seemedtoo much overcome to do anything but sit with its mouth open,gazing up into the roof of the court.

`What do you know about this business?’ the King said toAlice.

`Nothing,’ said Alice.

`Nothing WHATEVER?’ persisted the King.

`Nothing whatever,’ said Alice.

`That’s very important,’ the King said, turning to the jury.They were just beginning to write this down on their slates, whenthe White Rabbit interrupted: `UNimportant, your Majesty means,of course,’ he said in a very respectful tone, but frowning andmaking faces at him as he spoke.

`UNimportant, of course, I meant,’ the King hastily said, andwent on to himself in an undertone, `important–unimportant–unimportant–important–’ as if he were trying which wordsounded best.

Some of the jury wrote it down `important,’ and some`unimportant.’ Alice could see this, as she was near enough tolook over their slates; `but it doesn’t matter a bit,’ shethought to herself.

At this moment the King, who had been for some time busilywriting in his note-book, cackled out `Silence!’ and read outfrom his book, `Rule Forty-two. ALL PERSONS MORE THAN A MILEHIGH TO LEAVE THE COURT.’

Everybody looked at Alice.

`I’M not a mile high,’ said Alice.

`You are,’ said the King.

`Nearly two miles high,’ added the Queen.

`Well, I shan’t go, at any rate,’ said Alice: `besides,that’s not a regular rule: you invented it just now.’

`It’s the oldest rule in the book,’ said the King.`Then it ought to be Number One,’ said Alice.

The King turned pale, and shut his note-book hastily.`Consider your verdict,’ he said to the jury, in a low, tremblingvoice.

`There’s more evidence to come yet, please your Majesty,’ saidthe White Rabbit, jumping up in a great hurry; `this paper hasjust been picked up.’

`What’s in it?’ said the Queen.

`I haven’t opened it yet,’ said the White Rabbit, `but it seemsto be a letter, written by the prisoner to–to somebody.’

`It must have been that,’ said the King, `unless it waswritten to nobody, which isn’t usual, you know.’

`Who is it directed to?’ said one of the jurymen.

`It isn’t directed at all,’ said the White Rabbit; `in fact,there’s nothing written on the OUTSIDE.’ He unfolded the paperas he spoke, and added `It isn’t a letter, after all: it’s a setof verses.’

`Are they in the prisoner’s handwriting?’ asked another ofthe jurymen.

`No, they’re not,’ said the White Rabbit, `and that’s thequeerest thing about it.’ (The jury all looked puzzled.)

`He must have imitated somebody else’s hand,’ said the King.(The jury all brightened up again.)

`Please your Majesty,’ said the Knave, `I didn’t write it, andthey can’t prove I did: there’s no name signed at the end.’

`If you didn’t sign it,’ said the King, `that only makes thematter worse. You MUST have meant some mischief, or else you’dhave signed your name like an honest man.’

There was a general clapping of hands at this: it was thefirst really clever thing the King had said that day.

`That PROVES his guilt,’ said the Queen.

`It proves nothing of the sort!’ said Alice. `Why, you don’teven know what they’re about!’

`Read them,’ said the King.

The White Rabbit put on his spectacles. `Where shall I begin,please your Majesty?’ he asked.

`Begin at the beginning,’ the King said gravely, `and go ontill you come to the end: then stop.’

These were the verses the White Rabbit read:–

`They told me you had been to her, And mentioned me to him: She gave me a good character, But said I could not swim.

He sent them word I had not gone (We know it to be true): If she should push the matter on, What would become of you?

I gave her one, they gave him two, You gave us three or more; They all returned from him to you, Though they were mine before.

If I or she should chance to be Involved in this affair, He trusts to you to set them free, Exactly as we were.

My notion was that you had been (Before she had this fit) An obstacle that came between Him, and ourselves, and it.

Don’t let him know she liked them best, For this must ever be A secret, kept from all the rest, Between yourself and me.’

`That’s the most important piece of evidence we’ve heard yet,’said the King, rubbing his hands; `so now let the jury–’

`If any one of them can explain it,’ said Alice, (she hadgrown so large in the last few minutes that she wasn’t a bitafraid of interrupting him,) `I’ll give him sixpence. _I_ don’tbelieve there’s an atom of meaning in it.The jury all wrote down on their slates, `SHE doesn’t believethere’s an atom of meaning in it,’ but none of them attempted toexplain the paper.

`If there’s no meaning in it,’ said the King, `that saves aworld of trouble, you know, as we needn’t try to find any. Andyet I don’t know,’ he went on, spreading out the verses on hisknee, and looking at them with one eye; `I seem to see somemeaning in them, after all. “–SAID I COULD NOT SWIM–” youcan’t swim, can you?’ he added, turning to the Knave.

The Knave shook his head sadly. `Do I look like it?’ he said.(Which he certainly did NOT, being made entirely of cardboard.)

`All right, so far,’ said the King, and he went on mutteringover the verses to himself: `”WE KNOW IT TO BE TRUE–” that’sthe jury, of course– “I GAVE HER ONE, THEY GAVE HIM TWO–” why,that must be what he did with the tarts, you know–’

`But, it goes on “THEY ALL RETURNED FROM HIM TO YOU,”‘ saidAlice.

`Why, there they are!’ said the King triumphantly, pointing tothe tarts on the table. `Nothing can be clearer than THAT.Then again–”BEFORE SHE HAD THIS FIT–” you never had fits, mydear, I think?’ he said to the Queen.

`Never!’ said the Queen furiously, throwing an inkstand at theLizard as she spoke. (The unfortunate little Bill had left offwriting on his slate with one finger, as he found it made nomark; but he now hastily began again, using the ink, that wastrickling down his face, as long as it lasted.)

`Then the words don’t FIT you,’ said the King, looking roundthe court with a smile. There was a dead silence.

`It’s a pun!’ the King added in an offended tone, andeverybody laughed, `Let the jury consider their verdict,’ theKing said, for about the twentieth time that day.

`No, no!’ said the Queen. `Sentence first–verdict afterwards.’

`Stuff and nonsense!’ said Alice loudly. `The idea of havingthe sentence first!’

`Hold your tongue!’ said the Queen, turning purple.

`I won’t!’ said Alice.

`Off with her head!’ the Queen shouted at the top of her voice.Nobody moved.

`Who cares for you?’ said Alice, (she had grown to her fullsize by this time.) `You’re nothing but a pack of cards!’

At this the whole pack rose up into the air, and came flyingdown upon her: she gave a little scream, half of fright and halfof anger, and tried to beat them off, and found herself lying onthe bank, with her head in the lap of her sister, who was gentlybrushing away some dead leaves that had fluttered down from thetrees upon her face.

`Wake up, Alice dear!’ said her sister; `Why, what a longsleep you’ve had!’

`Oh, I’ve had such a curious dream!’ said Alice, and she toldher sister, as well as she could remember them, all these strangeAdventures of hers that you have just been reading about; andwhen she had finished, her sister kissed her, and said, `It WAS acurious dream, dear, certainly: but now run in to your tea; it’sgetting late.’ So Alice got up and ran off, thinking while sheran, as well she might, what a wonderful dream it had been.

But her sister sat still just as she left her, leaning herhead on her hand, watching the setting sun, and thinking oflittle Alice and all her wonderful Adventures, till she too begandreaming after a fashion, and this was her dream:–

First, she dreamed of little Alice herself, and once again thetiny hands were clasped upon her knee, and the bright eager eyeswere looking up into hers–she could hear the very tones of hervoice, and see that queer little toss of her head to keep backthe wandering hair that WOULD always get into her eyes–andstill as she listened, or seemed to listen, the whole placearound her became alive the strange creatures of her littlesister’s dream.

The long grass rustled at her feet as the White Rabbit hurriedby–the frightened Mouse splashed his way through theneighbouring pool–she could hear the rattle of the teacups asthe March Hare and his friends shared their never-ending meal,and the shrill voice of the Queen ordering off her unfortunateguests to execution–once more the pig-baby was sneezing on theDuchess’s knee, while plates and dishes crashed around it–oncemore the shriek of the Gryphon, the squeaking of the Lizard’sslate-pencil, and the choking of the suppressed guinea-pigs,filled the air, mixed up with the distant sobs of the miserableMock Turtle.

So she sat on, with closed eyes, and half believed herself inWonderland, though she knew she had but to open them again, andall would change to dull reality–the grass would be onlyrustling in the wind, and the pool rippling to the waving of thereeds–the rattling teacups would change to tinkling sheep-bells, and the Queen’s shrill cries to the voice of the shepherdboy–and the sneeze of the baby, the shriek of the Gryphon, andall the other queer noises, would change (she knew) to theconfused clamour of the busy farm-yard–while the lowing of thecattle in the distance would take the place of the Mock Turtle’sheavy sobs.

Lastly, she pictured to herself how this same little sister ofhers would, in the after-time, be herself a grown woman; and howshe would keep, through all her riper years, the simple andloving heart of her childhood: and how she would gather abouther other little children, and make THEIR eyes bright and eagerwith many a strange tale, perhaps even with the dream ofWonderland of long ago: and how she would feel with all theirsimple sorrows, and find a pleasure in all their simple joys,remembering her own child-life, and the happy summer days.

THE END

Alice in wonderland - Chapter 11

Download the MP3 Audio of Alice Chapter 11

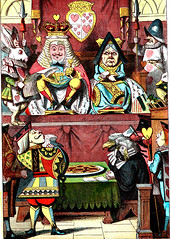

Who Stole the Tarts? We reach the last but one chapter of the first Alice book. The trial begins of the Knave of Hearts on the charge of stealing the tarts. Many familiar faces are present in the court room. The judge is the King, and his is assisted by the ferocious queen. The Mad Hatter gives some very nervous evidence, and is contradicted by the March Hare. The juror’s box is filled with small animals and birds who feaverishly take notes. Alice begins to doubt that justice really will be done.

Who Stole the Tarts? We reach the last but one chapter of the first Alice book. The trial begins of the Knave of Hearts on the charge of stealing the tarts. Many familiar faces are present in the court room. The judge is the King, and his is assisted by the ferocious queen. The Mad Hatter gives some very nervous evidence, and is contradicted by the March Hare. The juror’s box is filled with small animals and birds who feaverishly take notes. Alice begins to doubt that justice really will be done.

If you use iTunes you can now subscribe to our Alice Podcast by clicking here. Or catch it in a blog reader or podcatcher here.

Read by Natasha. Duration 14.15.

The King and Queen of Hearts were seated on their throne when

they arrived, with a great crowd assembled about them–all sorts

of little birds and beasts, as well as the whole pack of cards:

the Knave was standing before them, in chains, with a soldier on

each side to guard him; and near the King was the White Rabbit,

with a trumpet in one hand, and a scroll of parchment in the

other. In the very middle of the court was a table, with a large

dish of tarts upon it: they looked so good, that it made Alice

quite hungry to look at them–`I wish they’d get the trial done,’

she thought, `and hand round the refreshments!’ But there seemed

to be no chance of this, so she began looking at everything about

her, to pass away the time.

Alice had never been in a court of justice before, but she had

read about them in books, and she was quite pleased to find that

she knew the name of nearly everything there. `That’s the

judge,’ she said to herself, `because of his great wig.’

The judge, by the way, was the King; and as he wore his crown

over the wig, (look at the frontispiece if you want to see how he

did it,) he did not look at all comfortable, and it was certainly

not becoming.

`And that’s the jury-box,’ thought Alice, `and those twelve

creatures,’ (she was obliged to say `creatures,’ you see, because

some of them were animals, and some were birds,) `I suppose they

are the jurors.’ She said this last word two or three times over

to herself, being rather proud of it: for she thought, and

rightly too, that very few little girls of her age knew the

meaning of it at all. However, `jury-men’ would have done just

as well.

The twelve jurors were all writing very busily on slates.

`What are they doing?’ Alice whispered to the Gryphon. `They

can’t have anything to put down yet, before the trial’s begun.’

`They’re putting down their names,’ the Gryphon whispered in

reply, `for fear they should forget them before the end of the

trial.’

`Stupid things!’ Alice began in a loud, indignant voice, but

she stopped hastily, for the White Rabbit cried out, `Silence in

the court!’ and the King put on his spectacles and looked

anxiously round, to make out who was talking.

Alice could see, as well as if she were looking over their

shoulders, that all the jurors were writing down `stupid things!’

on their slates, and she could even make out that one of them

didn’t know how to spell `stupid,’ and that he had to ask his

neighbour to tell him. `A nice muddle their slates’ll be in

before the trial’s over!’ thought Alice.

One of the jurors had a pencil that squeaked. This of course,

Alice could not stand, and she went round the court and got

behind him, and very soon found an opportunity of taking it

away. She did it so quickly that the poor little juror (it was

Bill, the Lizard) could not make out at all what had become of

it; so, after hunting all about for it, he was obliged to write

with one finger for the rest of the day; and this was of very

little use, as it left no mark on the slate.

`Herald, read the accusation!’ said the King.

On this the White Rabbit blew three blasts on the trumpet, and

then unrolled the parchment scroll, and read as follows:–

`The Queen of Hearts, she made some tarts,

All on a summer day:

The Knave of Hearts, he stole those tarts,

And took them quite away!’

`Consider your verdict,’ the King said to the jury.

`Not yet, not yet!’ the Rabbit hastily interrupted. `There’s

a great deal to come before that!’

`Call the first witness,’ said the King; and the White Rabbit

blew three blasts on the trumpet, and called out, `First

witness!’

The first witness was the Hatter. He came in with a teacup in

one hand and a piece of bread-and-butter in the other. `I beg

pardon, your Majesty,’ he began, `for bringing these in: but I

hadn’t quite finished my tea when I was sent for.’

`You ought to have finished,’ said the King. `When did you

begin?’

The Hatter looked at the March Hare, who had followed him into

the court, arm-in-arm with the Dormouse. `Fourteenth of March, I

think it was,’ he said.

`Fifteenth,’ said the March Hare.

`Sixteenth,’ added the Dormouse.

`Write that down,’ the King said to the jury, and the jury

eagerly wrote down all three dates on their slates, and then

added them up, and reduced the answer to shillings and pence.

`Take off your hat,’ the King said to the Hatter.

`It isn’t mine,’ said the Hatter.

`Stolen!’ the King exclaimed, turning to the jury, who

instantly made a memorandum of the fact.

`I keep them to sell,’ the Hatter added as an explanation;

`I’ve none of my own. I’m a hatter.’

Here the Queen put on her spectacles, and began staring at the

Hatter, who turned pale and fidgeted.

`Give your evidence,’ said the King; `and don’t be nervous, or

I’ll have you executed on the spot.’

This did not seem to encourage the witness at all: he kept

shifting from one foot to the other, looking uneasily at the

Queen, and in his confusion he bit a large piece out of his

teacup instead of the bread-and-butter.

Just at this moment Alice felt a very curious sensation, which

puzzled her a good deal until she made out what it was: she was

beginning to grow larger again, and she thought at first she

would get up and leave the court; but on second thoughts she

decided to remain where she was as long as there was room for

her.

`I wish you wouldn’t squeeze so.’ said the Dormouse, who was

sitting next to her. `I can hardly breathe.’

`I can’t help it,’ said Alice very meekly: `I’m growing.’

`You’ve no right to grow here,’ said the Dormouse.

`Don’t talk nonsense,’ said Alice more boldly: `you know

you’re growing too.’

`Yes, but I grow at a reasonable pace,’ said the Dormouse:

`not in that ridiculous fashion.’ And he got up very sulkily

and crossed over to the other side of the court.

All this time the Queen had never left off staring at the

Hatter, and, just as the Dormouse crossed the court, she said to

one of the officers of the court, `Bring me the list of the

singers in the last concert!’ on which the wretched Hatter

trembled so, that he shook both his shoes off.

`Give your evidence,’ the King repeated angrily, `or I’ll have

you executed, whether you’re nervous or not.’

`I’m a poor man, your Majesty,’ the Hatter began, in a

trembling voice, `–and I hadn’t begun my tea–not above a week

or so–and what with the bread-and-butter getting so thin–and

the twinkling of the tea–’

`The twinkling of the what?’ said the King.

`It began with the tea,’ the Hatter replied.

`Of course twinkling begins with a T!’ said the King sharply.

`Do you take me for a dunce? Go on!’

`I’m a poor man,’ the Hatter went on, `and most things

twinkled after that–only the March Hare said–’

`I didn’t!’ the March Hare interrupted in a great hurry.

`You did!’ said the Hatter.

`I deny it!’ said the March Hare.

`He denies it,’ said the King: `leave out that part.’

`Well, at any rate, the Dormouse said–’ the Hatter went on,

looking anxiously round to see if he would deny it too: but the

Dormouse denied nothing, being fast asleep.

`After that,’ continued the Hatter, `I cut some more bread-

and-butter–’

`But what did the Dormouse say?’ one of the jury asked.

`That I can’t remember,’ said the Hatter.

`You MUST remember,’ remarked the King, `or I’ll have you

executed.’

The miserable Hatter dropped his teacup and bread-and-butter,

and went down on one knee. `I’m a poor man, your Majesty,’ he

began.

`You’re a very poor speaker,’ said the King.

Here one of the guinea-pigs cheered, and was immediately

suppressed by the officers of the court. (As that is rather a

hard word, I will just explain to you how it was done. They had

a large canvas bag, which tied up at the mouth with strings:

into this they slipped the guinea-pig, head first, and then sat

upon it.)

`I’m glad I’ve seen that done,’ thought Alice. `I’ve so often

read in the newspapers, at the end of trials, “There was some

attempts at applause, which was immediately suppressed by the

officers of the court,” and I never understood what it meant

till now.’

`If that’s all you know about it, you may stand down,’

continued the King.

`I can’t go no lower,’ said the Hatter: `I’m on the floor, as

it is.’

`Then you may SIT down,’ the King replied.

Here the other guinea-pig cheered, and was suppressed.

`Come, that finished the guinea-pigs!’ thought Alice. `Now we

shall get on better.’

`I’d rather finish my tea,’ said the Hatter, with an anxious

look at the Queen, who was reading the list of singers.

`You may go,’ said the King, and the Hatter hurriedly left the

court, without even waiting to put his shoes on.

`–and just take his head off outside,’ the Queen added to one

of the officers: but the Hatter was out of sight before the

officer could get to the door.

`Call the next witness!’ said the King.

The next witness was the Duchess’s cook. She carried the

pepper-box in her hand, and Alice guessed who it was, even before

she got into the court, by the way the people near the door began

sneezing all at once.

`Give your evidence,’ said the King.

`Shan’t,’ said the cook.

The King looked anxiously at the White Rabbit, who said in a

low voice, `Your Majesty must cross-examine THIS witness.’

`Well, if I must, I must,’ the King said, with a melancholy

air, and, after folding his arms and frowning at the cook till

his eyes were nearly out of sight, he said in a deep voice, `What

are tarts made of?’

`Pepper, mostly,’ said the cook.

`Treacle,’ said a sleepy voice behind her.

`Collar that Dormouse,’ the Queen shrieked out. `Behead that

Dormouse! Turn that Dormouse out of court! Suppress him! Pinch

him! Off with his whiskers!’

For some minutes the whole court was in confusion, getting the

Dormouse turned out, and, by the time they had settled down

again, the cook had disappeared.

`Never mind!’ said the King, with an air of great relief.

`Call the next witness.’ And he added in an undertone to the

Queen, `Really, my dear, YOU must cross-examine the next witness.

It quite makes my forehead ache!’

Alice watched the White Rabbit as he fumbled over the list,

feeling very curious to see what the next witness would be like,

`–for they haven’t got much evidence YET,’ she said to herself.

Imagine her surprise, when the White Rabbit read out, at the top

of his shrill little voice, the name `Alice!’

Alice in wonderland - Chapter 10

Download the mp3 audio of Alice 10 (right click, save as)

According to the Wikipedia, a quadrille is ” a historic dance performed by four couples in a square formation.”

In this story it is performed by the Mock Turtle and The Gryffon, and there is a song about a fish (a whiting) and a lobster. In short, this is a very strange and quite musical episode.

Newbies can find the first chapter here.

Don’t miss our Alice pictures on Flickr.

Read by Natasha. Duration 21 minutes.

The Mock Turtle sighed deeply, and drew the back of one flapper

across his eyes. He looked at Alice, and tried to speak, but for

a minute or two sobs choked his voice. `Same as if he had a bone

in his throat,’ said the Gryphon: and it set to work shaking him

and punching him in the back. At last the Mock Turtle recovered

his voice, and, with tears running down his cheeks, he went on

again:–

`You may not have lived much under the sea–’ (`I haven’t,’ said Alice)–

`and perhaps you were never even introduced to a lobster–’

(Alice began to say `I once tasted–’ but checked herself hastily,

and said `No, never’) `–so you can have no idea what a delightful

thing a Lobster Quadrille is!’

`No, indeed,’ said Alice. `What sort of a dance is it?’

`Why,’ said the Gryphon, `you first form into a line along the sea-shore–’

`Two lines!’ cried the Mock Turtle. `Seals, turtles, salmon, and so on;

then, when you’ve cleared all the jelly-fish out of the way–’

`THAT generally takes some time,’ interrupted the Gryphon.

`–you advance twice–’

`Each with a lobster as a partner!’ cried the Gryphon.

`Of course,’ the Mock Turtle said: `advance twice, set to

partners–’

`–change lobsters, and retire in same order,’ continued the

Gryphon.

`Then, you know,’ the Mock Turtle went on, `you throw the–’

`The lobsters!’ shouted the Gryphon, with a bound into the air.

`–as far out to sea as you can–’

`Swim after them!’ screamed the Gryphon.

`Turn a somersault in the sea!’ cried the Mock Turtle,

capering wildly about.

`Change lobsters again!’ yelled the Gryphon at the top of its voice.

`Back to land again, and that’s all the first figure,’ said the

Mock Turtle, suddenly dropping his voice; and the two creatures,

who had been jumping about like mad things all this time, sat

down again very sadly and quietly, and looked at Alice.

`It must be a very pretty dance,’ said Alice timidly.

`Would you like to see a little of it?’ said the Mock Turtle.

`Very much indeed,’ said Alice.

`Come, let’s try the first figure!’ said the Mock Turtle to the

Gryphon. `We can do without lobsters, you know. Which shall

sing?’

`Oh, YOU sing,’ said the Gryphon. `I’ve forgotten the words.’

So they began solemnly dancing round and round Alice, every now

and then treading on her toes when they passed too close, and

waving their forepaws to mark the time, while the Mock Turtle

sang this, very slowly and sadly:–

`”Will you walk a little faster?” said a whiting to a snail.

“There’s a porpoise close behind us, and he’s treading on my

tail.

See how eagerly the lobsters and the turtles all advance!

They are waiting on the shingle–will you come and join the

dance?

Will you, won’t you, will you, won’t you, will you join the

dance?

Will you, won’t you, will you, won’t you, won’t you join the

dance?

“You can really have no notion how delightful it will be

When they take us up and throw us, with the lobsters, out to

sea!”

But the snail replied “Too far, too far!” and gave a look

askance–

Said he thanked the whiting kindly, but he would not join the

dance.

Would not, could not, would not, could not, would not join

the dance.

Would not, could not, would not, could not, could not join

the dance.

`”What matters it how far we go?” his scaly friend replied.

“There is another shore, you know, upon the other side.

The further off from England the nearer is to France–

Then turn not pale, beloved snail, but come and join the dance.

Will you, won’t you, will you, won’t you, will you join the

dance?

Will you, won’t you, will you, won’t you, won’t you join the

dance?”‘

`Thank you, it’s a very interesting dance to watch,’ said

Alice, feeling very glad that it was over at last: `and I do so

like that curious song about the whiting!’

`Oh, as to the whiting,’ said the Mock Turtle, `they–you’ve

seen them, of course?’

`Yes,’ said Alice, `I’ve often seen them at dinn–’ she

checked herself hastily.

`I don’t know where Dinn may be,’ said the Mock Turtle, `but

if you’ve seen them so often, of course you know what they’re

like.’

`I believe so,’ Alice replied thoughtfully. `They have their

tails in their mouths–and they’re all over crumbs.’

`You’re wrong about the crumbs,’ said the Mock Turtle:

`crumbs would all wash off in the sea. But they HAVE their tails

in their mouths; and the reason is–’ here the Mock Turtle

yawned and shut his eyes.–`Tell her about the reason and all

that,’ he said to the Gryphon.

`The reason is,’ said the Gryphon, `that they WOULD go with

the lobsters to the dance. So they got thrown out to sea. So

they had to fall a long way. So they got their tails fast in

their mouths. So they couldn’t get them out again. That’s all.’

`Thank you,’ said Alice, `it’s very interesting. I never knew

so much about a whiting before.’

`I can tell you more than that, if you like,’ said the

Gryphon. `Do you know why it’s called a whiting?’

`I never thought about it,’ said Alice. `Why?’

`IT DOES THE BOOTS AND SHOES.’ the Gryphon replied very

solemnly.

Alice was thoroughly puzzled. `Does the boots and shoes!’ she

repeated in a wondering tone.

`Why, what are YOUR shoes done with?’ said the Gryphon. `I

mean, what makes them so shiny?’

Alice looked down at them, and considered a little before she

gave her answer. `They’re done with blacking, I believe.’

`Boots and shoes under the sea,’ the Gryphon went on in a deep

voice, `are done with a whiting. Now you know.’

`And what are they made of?’ Alice asked in a tone of great

curiosity.

`Soles and eels, of course,’ the Gryphon replied rather

impatiently: `any shrimp could have told you that.’

`If I’d been the whiting,’ said Alice, whose thoughts were

still running on the song, `I’d have said to the porpoise, “Keep

back, please: we don’t want YOU with us!”‘

`They were obliged to have him with them,’ the Mock Turtle

said: `no wise fish would go anywhere without a porpoise.’

`Wouldn’t it really?’ said Alice in a tone of great surprise.

`Of course not,’ said the Mock Turtle: `why, if a fish came

to ME, and told me he was going a journey, I should say “With

what porpoise?”‘

`Don’t you mean “purpose”?’ said Alice.

`I mean what I say,’ the Mock Turtle replied in an offended

tone. And the Gryphon added `Come, let’s hear some of YOUR

adventures.’

`I could tell you my adventures–beginning from this morning,’

said Alice a little timidly: `but it’s no use going back to

yesterday, because I was a different person then.’

`Explain all that,’ said the Mock Turtle.

`No, no! The adventures first,’ said the Gryphon in an

impatient tone: `explanations take such a dreadful time.’

So Alice began telling them her adventures from the time when

she first saw the White Rabbit. She was a little nervous about

it just at first, the two creatures got so close to her, one on

each side, and opened their eyes and mouths so VERY wide, but she

gained courage as she went on. Her listeners were perfectly

quiet till she got to the part about her repeating `YOU ARE OLD,

FATHER WILLIAM,’ to the Caterpillar, and the words all coming

different, and then the Mock Turtle drew a long breath, and said

`That’s very curious.’

`It’s all about as curious as it can be,’ said the Gryphon.

`It all came different!’ the Mock Turtle repeated

thoughtfully. `I should like to hear her try and repeat

something now. Tell her to begin.’ He looked at the Gryphon as

if he thought it had some kind of authority over Alice.

`Stand up and repeat “‘TIS THE VOICE OF THE SLUGGARD,”‘ said

the Gryphon.

`How the creatures order one about, and make one repeat

lessons!’ thought Alice; `I might as well be at school at once.’

However, she got up, and began to repeat it, but her head was so

full of the Lobster Quadrille, that she hardly knew what she was

saying, and the words came very queer indeed:–

`’Tis the voice of the Lobster; I heard him declare,

“You have baked me too brown, I must sugar my hair.”

As a duck with its eyelids, so he with his nose

Trims his belt and his buttons, and turns out his toes.’

[later editions continued as follows

When the sands are all dry, he is gay as a lark,

And will talk in contemptuous tones of the Shark,

But, when the tide rises and sharks are around,

His voice has a timid and tremulous sound.]

`That’s different from what I used to say when I was a child,’

said the Gryphon.

`Well, I never heard it before,’ said the Mock Turtle; `but it

sounds uncommon nonsense.’

Alice said nothing; she had sat down with her face in her

hands, wondering if anything would EVER happen in a natural way

again.

`I should like to have it explained,’ said the Mock Turtle.

`She can’t explain it,’ said the Gryphon hastily. `Go on with

the next verse.’

`But about his toes?’ the Mock Turtle persisted. `How COULD

he turn them out with his nose, you know?’

`It’s the first position in dancing.’ Alice said; but was

dreadfully puzzled by the whole thing, and longed to change the

subject.

`Go on with the next verse,’ the Gryphon repeated impatiently:

`it begins “I passed by his garden.”‘

Alice did not dare to disobey, though she felt sure it would

all come wrong, and she went on in a trembling voice:–

`I passed by his garden, and marked, with one eye,

How the Owl and the Panther were sharing a pie–’

[later editions continued as follows

The Panther took pie-crust, and gravy, and meat,

While the Owl had the dish as its share of the treat.

When the pie was all finished, the Owl, as a boon,

Was kindly permitted to pocket the spoon:

While the Panther received knife and fork with a growl,

And concluded the banquet--]

`What IS the use of repeating all that stuff,’ the Mock Turtle

interrupted, `if you don’t explain it as you go on? It’s by far

the most confusing thing I ever heard!’

`Yes, I think you’d better leave off,’ said the Gryphon: and

Alice was only too glad to do so.

`Shall we try another figure of the Lobster Quadrille?’ the

Gryphon went on. `Or would you like the Mock Turtle to sing you

a song?’

`Oh, a song, please, if the Mock Turtle would be so kind,’

Alice replied, so eagerly that the Gryphon said, in a rather

offended tone, `Hm! No accounting for tastes! Sing her

“Turtle Soup,” will you, old fellow?’

The Mock Turtle sighed deeply, and began, in a voice sometimes

choked with sobs, to sing this:–

`Beautiful Soup, so rich and green,

Waiting in a hot tureen!

Who for such dainties would not stoop?

Soup of the evening, beautiful Soup!

Soup of the evening, beautiful Soup!

Beau–ootiful Soo–oop!

Beau–ootiful Soo–oop!

Soo–oop of the e–e–evening,

Beautiful, beautiful Soup!

`Beautiful Soup! Who cares for fish,

Game, or any other dish?

Who would not give all else for two

Pennyworth only of beautiful Soup?

Pennyworth only of beautiful Soup?

Beau–ootiful Soo–oop!

Beau–ootiful Soo–oop!

Soo–oop of the e–e–evening,

Beautiful, beauti–FUL SOUP!’

`Chorus again!’ cried the Gryphon, and the Mock Turtle had

just begun to repeat it, when a cry of `The trial’s beginning!’

was heard in the distance.

`Come on!’ cried the Gryphon, and, taking Alice by the hand,

it hurried off, without waiting for the end of the song.

`What trial is it?’ Alice panted as she ran; but the Gryphon

only answered `Come on!’ and ran the faster, while more and more

faintly came, carried on the breeze that followed them, the

melancholy words:–

`Soo–oop of the e–e–evening,

Beautiful, beautiful Soup!’Alice in wonderland - Chapter 9

Download the MP3 Audio of Alice 9 (Right Click, Save Link as)

The Mock Turtle’s Story Alice, still holding a flamingo under her arm, returns to the Duchess and is irritated by her sharp chin and her constant refrain, ‘And the moral of that is…’. Next we meet a Gryphon and a Mock Turtle. (A Gryphon is a mythological creature and a mock turtle was a type of Victorian Soup - a poor version of Turtle Soup.) The Gryphon and the rather miserable Mock Turtle talk about their school days and are rather prone to schoolboy puns.

The Mock Turtle’s Story Alice, still holding a flamingo under her arm, returns to the Duchess and is irritated by her sharp chin and her constant refrain, ‘And the moral of that is…’. Next we meet a Gryphon and a Mock Turtle. (A Gryphon is a mythological creature and a mock turtle was a type of Victorian Soup - a poor version of Turtle Soup.) The Gryphon and the rather miserable Mock Turtle talk about their school days and are rather prone to schoolboy puns.

Apologies to Alice fans for the long delay in publishing this chapter.

Duration 20 minutes. Read by Natasha.

You can’t think how glad I am to see you again, you dear old thing!’ said the Duchess, as she tucked her arm affectionately into Alice’s, and they walked off together.

Alice was very glad to find her in such a pleasant temper, and thought to herself that perhaps it was only the pepper that had made her so savage when they met in the kitchen.

‘When I’m a Duchess,’ she said to herself, (not in a very hopeful tone though), ‘I won’t have any pepper in my kitchen at all. Soup does very well without—Maybe it’s always pepper that makes people hot-tempered,’ she went on, very much pleased at having found out a new kind of rule, ‘and vinegar that makes them sour—and camomile that makes them bitter—and—and barley-sugar and such things that make children sweet-tempered. I only wish people knew that: then they wouldn’t be so stingy about it, you know–’

She had quite forgotten the Duchess by this time, and was a little startled when she heard her voice close to her ear. ‘You’re thinking about something, my dear, and that makes you forget to talk. I can’t tell you just now what the moral of that is, but I shall remember it in a bit.’

‘Perhaps it hasn’t one,’ Alice ventured to remark.

‘Tut, tut, child!’ said the Duchess. ‘Everything’s got a moral, if only you can find it.’ And she squeezed herself up closer to Alice’s side as she spoke.

Alice did not much like keeping so close to her: first, because the Duchess was very ugly; and secondly, because she was exactly the right height to rest her chin upon Alice’s shoulder, and it was an uncomfortably sharp chin. However, she did not like to be rude, so she bore it as well as she could.

‘The game’s going on rather better now,’ she said, by way of keeping up the conversation a little.

”Tis so,’ said the Duchess: ‘and the moral of that is—”Oh, ’tis love, ’tis love, that makes the world go round!”‘

‘Somebody said,’ Alice whispered, ‘that it’s done by everybody minding their own business!’

‘Ah, well! It means much the same thing,’ said the Duchess, digging her sharp little chin into Alice’s shoulder as she added, ‘and the moral of that is—”Take care of the sense, and the sounds will take care of themselves.”‘

‘How fond she is of finding morals in things!’ Alice thought to herself.

‘I dare say you’re wondering why I don’t put my arm round your waist,’ the Duchess said after a pause: ‘the reason is, that I’m doubtful about the temper of your flamingo. Shall I try the experiment?’

‘He might bite,’ Alice cautiously replied, not feeling at all anxious to have the experiment tried.

‘Very true,’ said the Duchess: ‘flamingoes and mustard both bite. And the moral of that is—”Birds of a feather flock together.”‘

‘Only mustard isn’t a bird,’ Alice remarked.

‘Right, as usual,’ said the Duchess: ‘what a clear way you have of putting things!’

‘It’s a mineral, I think,’ said Alice.

‘Of course it is,’ said the Duchess, who seemed ready to agree to everything that Alice said; ‘there’s a large mustard-mine near here. And the moral of that is—”The more there is of mine, the less there is of yours.”‘

‘Oh, I know!’ exclaimed Alice, who had not attended to this last remark, ‘it’s a vegetable. It doesn’t look like one, but it is.’

‘I quite agree with you,’ said the Duchess; ‘and the moral of that is—”Be what you would seem to be”—or if you’d like it put more simply—”Never imagine yourself not to be otherwise than what it might appear to others that what you were or might have been was not otherwise than what you had been would have appeared to them to be otherwise.”‘

‘I think I should understand that better,’ Alice said very politely, ‘if I had it written down: but I can’t quite follow it as you say it.’

‘That’s nothing to what I could say if I chose,’ the Duchess replied, in a pleased tone.

‘Pray don’t trouble yourself to say it any longer than that,’ said Alice.

‘Oh, don’t talk about trouble!’ said the Duchess. ‘I make you a present of everything I’ve said as yet.’

‘A cheap sort of present!’ thought Alice. ‘I’m glad they don’t give birthday presents like that!’ But she did not venture to say it out loud.

‘Thinking again?’ the Duchess asked, with another dig of her sharp little chin.

‘I’ve a right to think,’ said Alice sharply, for she was beginning to feel a little worried.

‘Just about as much right,’ said the Duchess, ‘as pigs have to fly; and the m—’

But here, to Alice’s great surprise, the Duchess’s voice died away, even in the middle of her favourite word ‘moral,’ and the arm that was linked into hers began to tremble. Alice looked up, and there stood the Queen in front of them, with her arms folded, frowning like a thunderstorm.

‘A fine day, your Majesty!’ the Duchess began in a low, weak voice.

‘Now, I give you fair warning,’ shouted the Queen, stamping on the ground as she spoke; ‘either you or your head must be off, and that in about half no time! Take your choice!’

The Duchess took her choice, and was gone in a moment.

‘Let’s go on with the game,’ the Queen said to Alice; and Alice was too much frightened to say a word, but slowly followed her back to the croquet-ground.

The other guests had taken advantage of the Queen’s absence, and were resting in the shade: however, the moment they saw her, they hurried back to the game, the Queen merely remarking that a moment’s delay would cost them their lives.

All the time they were playing the Queen never left off quarrelling with the other players, and shouting ‘Off with his head!’ or ‘Off with her head!’ Those whom she sentenced were taken into custody by the soldiers, who of course had to leave off being arches to do this, so that by the end of half an hour or so there were no arches left, and all the players, except the King, the Queen, and Alice, were in custody and under sentence of execution.

Then the Queen left off, quite out of breath, and said to Alice, ‘Have you seen the Mock Turtle yet?’

‘No,’ said Alice. ‘I don’t even know what a Mock Turtle is.’

‘It’s the thing Mock Turtle Soup is made from,’ said the Queen.

‘I never saw one, or heard of one,’ said Alice.

‘Come on, then,’ said the Queen, ‘and he shall tell you his history,’

As they walked off together, Alice heard the King say in a low voice, to the company generally, ‘You are all pardoned.’ ‘Come, that’s a good thing!’ she said to herself, for she had felt quite unhappy at the number of executions the Queen had ordered.

They very soon came upon a Gryphon, lying fast asleep in the sun.

They had not gone far before they saw the Mock Turtle in the distance, sitting sad and lonely on a little ledge of rock, and, as they came nearer, Alice could hear him sighing as if his heart would break. She pitied him deeply. ‘What is his sorrow?’ she asked the Gryphon, and the Gryphon answered, very nearly in the same words as before, ‘It’s all his fancy, that: he hasn’t got no sorrow, you know. Come on!’

So they went up to the Mock Turtle, who looked at them with large eyes full of tears, but said nothing.

‘This here young lady,’ said the Gryphon, ’she wants for to know your history, she do.’

‘I’ll tell it her,’ said the Mock Turtle in a deep, hollow tone: ’sit down, both of you, and don’t speak a word till I’ve finished.’

So they sat down, and nobody spoke for some minutes. Alice thought to herself, ‘I don’t see how he can even finish, if he doesn’t begin.’ But she waited patiently.

‘Once,’ said the Mock Turtle at last, with a deep sigh, ‘I was a real Turtle.’

These words were followed by a very long silence, broken only by an occasional exclamation of ‘Hjckrrh!’ from the Gryphon, and the constant heavy sobbing of the Mock Turtle. Alice was very nearly getting up and saying, ‘Thank you, sir, for your interesting story,’ but she could not help thinking there must be more to come, so she sat still and said nothing.

‘When we were little,’ the Mock Turtle went on at last, more calmly, though still sobbing a little now and then, ‘we went to school in the sea. The master was an old Turtle—we used to call him Tortoise—’

‘Why did you call him Tortoise, if he wasn’t one?’ Alice asked.

‘We called him Tortoise because he taught us,’ said the Mock Turtle angrily: ‘really you are very dull!’

‘You ought to be ashamed of yourself for asking such a simple question,’ added the Gryphon; and then they both sat silent and looked at poor Alice, who felt ready to sink into the earth. At last the Gryphon said to the Mock Turtle, ‘Drive on, old fellow! Don’t be all day about it!’ and he went on in these words:

‘Yes, we went to school in the sea, though you mayn’t believe it—’

‘I never said I didn’t!’ interrupted Alice.

‘You did,’ said the Mock Turtle.

‘Hold your tongue!’ added the Gryphon, before Alice could speak again. The Mock Turtle went on.

‘We had the best of educations—in fact, we went to school every day—’

‘I’ve been to a day-school, too,’ said Alice; ‘you needn’t be so proud as all that.’

‘With extras?’ asked the Mock Turtle a little anxiously.

‘Yes,’ said Alice, ‘we learned French and music.’

‘And washing?’ said the Mock Turtle.

‘Certainly not!’ said Alice indignantly.

‘Ah! then yours wasn’t a really good school,’ said the Mock Turtle in a tone of great relief. ‘Now at ours they had at the end of the bill, “French, music, and washing—extra.”‘

‘You couldn’t have wanted it much,’ said Alice; ‘living at the bottom of the sea.’

‘I couldn’t afford to learn it.’ said the Mock Turtle with a sigh. ‘I only took the regular course.’

‘What was that?’ inquired Alice.

‘Reeling and Writhing, of course, to begin with,’ the Mock Turtle replied; ‘and then the different branches of Arithmetic— Ambition, Distraction, Uglification, and Derision.’

‘I never heard of “Uglification,”‘ Alice ventured to say. ‘What is it?’

The Gryphon lifted up both its paws in surprise. ‘What! Never heard of uglifying!’ it exclaimed. ‘You know what to beautify is, I suppose?’

‘Yes,’ said Alice doubtfully: ‘it means—to—make—anything—prettier.’